Trigger warning: This blog mentions physical and sexual violence against women and children.

In the 2024 Women and Men Fact Sheet released by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), results showed a disturbing number of 19,228 women aged 15-49 have experienced various forms of physical and sexual violence. This 2022 National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) by the PSA tells of an alarming fact that violence against women and children (VAWC) persists in the Philippines.

As of February 2024, there was a total of 16.9% increase in the cases reported to the Philippine National Police Crime Information, Reporting and Analysis System (PNP CIRAS) from 11,307 cases in 2022 to 13,213 cases in 2023. A number of 7,161 cases in 2022 and 7,764 in 2023 (8.4% increase) are violations against Republic Act No. 9262, or the Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004.

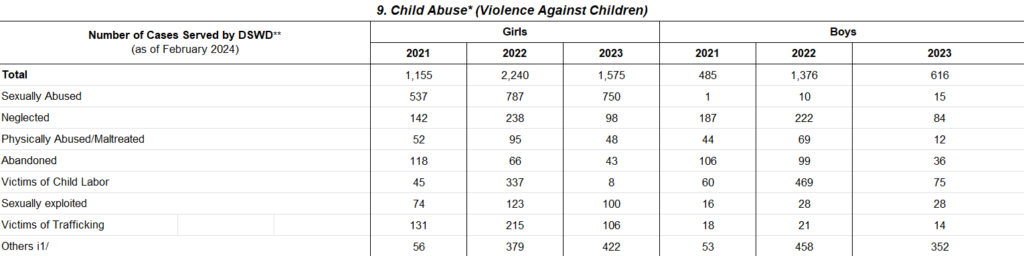

Additionally, 2,191 cases (1,575 girls and 616 boys) of child abuse or violence against children were reportedly served by the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) in 2023. This is a 39.4% decrease from the previous 3,616 cases in 2022, however, the point stands that this is still a serious problem in the country.

“Violence against women (VAW) appears as one of the country’s pervasive social problems,” said the Philippine Commission on Women (PCW), the government-mandated agency at the center of women’s and children’s rights supervision, enforcement, and protection.

As such, this Women’s Month and the upcoming celebration of Girl Child Week per Proclamation No. 759, s. of 1996, awareness of women’s and children’s rights and the laws that protect them is once again underscored.

Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004 (RA 9262)

The Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004, or simply the Anti-VAWC Act, seeks to recognize and address the need to protect the family and its members particularly women and children, from violence and threats to their safety and security.

According to the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women in 1993, VAW is “any act of gender-based violence that results in or is likely to result in physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public and private life. Gender-based violence is any violence inflicted on women because of their sex.”

Following this and other international human rights instruments to which the Philippines is a party, the Anti-VAWC Act defines ‘violence against women and children’ as any act or a series of acts committed by any person

- against a woman who is his wife, former wife, or

- against a woman with whom the person has had a sexual or dating relationship, or with whom he has a common child, or

- against her child whether legitimate or illegitimate, within or without the family abode .

which result in or is likely to result in physical, sexual, psychological harm or suffering, or economic abuse

What is considered VAWC under the Anti-VAWC Act?

VAWC includes:

- Physical violence. Acts that include bodily or physical harm.

- Sexual violence. Acts which are sexual in nature, committed against a woman or her child, which includes but is not limited to:

- Rape or sexual assault

- Harassment, threats, or intimidation to engage in sexual activity

- Forcing a woman or child to engage in prostitution or pornography

- Treating a partner as a sexual object

- Psychological violence. Acts or omissions causing or likely to cause mental or emotional suffering of the victim such as, but not limited to:

- Intimidation

- Harassment

- Stalking

- Damage to property

- Public ridicule or humiliation

- Repeated verbal abuse

- Marital infidelity

Likewise, Section 5 of the Act clarifies which acts qualify as a crime of VAWC. These include the following:

- Threatening, attempting, or outright causing physical harm to the woman or her child

- Placing the woman or her child in fear of imminent physical harm

- Trying to force the woman or her child to do something through force, threat of any type of harm, or intimidation

- Restricting the woman or her child from doing something through force, threat of any type of harm, or intimidation. These include depriving or threatening to deprive the victim of: custody of her/his family; financial support; a legal right; his/her control of his/her own money or properties; and the right to enter a legitimate profession, occupation, or business

- Inflicting or threatening to inflict self-harm to control her actions or decisions

- Forcing or intimidating the woman or her child into engaging in any sexual activity that does not constitute rape

- Doing anything that alarms or causes emotional or psychological distress to the woman or her child, such as following them in public or private places, lingering outside their home, entering or remaining in their home against their will, destroying their property, hurting their pets, or engaging in any other form of harassment or violence.

- Causing mental or emotional anguish, public ridicule, or humiliation to the woman or her child. This includes but is not limited to verbal and emotional abuse, denial of financial support, or denial of custody or access to the woman’s child/children.

Penalties against violations and crimes under Anti-VAWC Act

The penalties of committing an act listed in RA 9262 vary and depend on the severity of the act.

- A perpetrator is subject to prison for one (1) month and one (1) day to six (6) months if he or she attempted to harm the woman or her child or place them in fear of imminent physical harm, or threatens to self-harm to control their actions or decisions.

- A perpetrator is subject to prison for six (6) months and one (1) day to six (6) years if he or she restricted the victim from doing something, or forced him or her into doing something through force or intimidation.

- A perpetrator is subject to prison for six (6) years and one (1) day to twelve (12) years if he or she attempted to or did any form of sexual violence on the victim; caused emotional or psychological distress to the victim through behaviors such as stalking, destroying the victim’s property, etc.; or causing mental or emotional anguish, public ridicule, or humiliation to the victim.

| Act of Violence | Duration of Penalty |

| Attempt to harm the victim | 1 month and 1 day – 6 months |

| Place the victim in fear of imminent physical harm | 1 month and 1 day – 6 months |

| Threaten to or does self-harm to control the victim’s actions or decisions | 1 month and 1 day – 6 months |

| Restrict the victim from doing something through force or intimidation | 6 months and 1 day – 6 years |

| Force the victim into doing something through force or intimidation | 6 months and 1 day – 6 years |

| Attempt to or do any form of sexual violence on the victim | 6 years and 1 day – 12 years |

| Cause emotional or psychological distress to the victim through behaviors such as stalking, destroying the victims property, etc. | 6 years and 1 day – 12 years |

| Cause mental or emotional anguish, public ridicule, or humiliation to the victim | 6 years and 1 day – 12 years |

| If the acts are committed while the woman or child is pregnant or committed in the presence of her child, the penalty to be applied shall be the maximum period of penalty prescribed in the section. | |

| In addition to imprisonment, the perpetrator shall pay a fine of not less than P100,000.00, but not more than ₱300,000.00. He or she must also undergo mandatory psychological counseling or psychiatric treatment and shall report compliance to the court. | |

Protection Orders

While a victim can file a case against his or her perpetrator for his or her act of violence, it doesn’t guarantee with certainty that the perpetrator won’t endanger the victim again. To prevent this from happening, the victim can apply for a protection order.

A protection order prevents further acts of violence against a woman or her child. It also provides these victims other forms of necessary relief. A protection order aims to safeguard the victim from further harm, minimizes disruption in the victim’s daily life, and facilitates the victim’s opportunity and ability to independently regain control over her life. There are three types of protection orders that may be issued under this Act: the barangay protection order (BPO), temporary protection order (TPO) and permanent protection order (PPO).

Barangay Protection Orders, or BPOs, refer to the protection order issued by the Punong Barangay ordering the perpetrator to desist. A Punong Barangay shall issue the protection order to the applicant on the date of filing. If the Punong Barangay is unavailable to act on the BPO application, the application shall be acted upon by any available Barangay Kagawad. BPOs are effective for fifteen days.

Temporary Protection Orders, or TPOs, refer to the protection order issued by the court on the date of filing of the application. They are effective for thirty days. The court shall also schedule a hearing on the issuance of a PPO prior to or on the TPO’s expiration date.

Permanent Protection Orders, or PPOs, refer to protection orders issued by the court after a notice and hearing. The court shall conduct the hearing on the merits of the issuance of a PPO in one day. If the court is unable to conduct the hearing within one day and the TPO issued before is due to expire, the court shall continuously extend or renew the TPO for a period of thirty days.

These protection orders shall include any, some, or all of the following reliefs:

- prohibition of the perpetrator from committing or threatening to commit another act of violence towards the victim

- prohibition of the perpetrator from communicating with the victim, directly or indirectly

- removal of the perpetrator from the residence of the victim, regardless of owner of the residence

- directing the perpetrator to stay away from the victim up to a certain distance specified by the court. The perpetrator must always stay from the residence, school, place of employment, or any specific place frequented by the victim.

- All TPOs and PPOs issued under this act shall be enforceable anywhere in the Philippines. A violation shall be punishable with a fine ranging from ₱5,000.00 to ₱50,000.00 and/or imprisonment of six (6) months.

An application for a TPO or PPO shall be filed with the appropriate Regional Trial Court (RTC), Family Court, or Municipal Trial Court (MTC) of the victim’s place of residence. Meanwhile, a victim can apply for a BPO in the Barangay where they reside.

The application for a protection order must be in writing, signed and verified under oath by the applicant. A standard application form should contain, among others the following information:

- Names and addresses of the perpetrator and victim;

- Description of the two parties’ relationships;

- A statement on the circumstances of the abuse;

- Description of the reliefs requested by the victim;

- Request for counsel and reasons for such;

- Request for waiver of application fees until hearing; and

- An attestation that there is no pending application for a protection order in another court.

Other parties can also file the Petition for Protection Order in the victim’s stead. These include his or her parents; other relatives within the fourth civil degree of consanguinity or affinity; social workers; police officers; Punong Barangay or Barangay Kagawad; the victim’s lawyer, counselor, therapist, or healthcare provider; or at least two concerned citizens of the municipality who have personal knowledge of the offense committed.

Disclaimer: The content of this blog is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered as legal advice. While we strive to provide accurate and up-to-date information, the blog does not create an attorney-client relationship. For legal concerns or specific legal guidance, please consult a qualified lawyer.

To read more STLAF legal tidbits, visit www.sadsadtamesislaw.com/bits-of-law.

For comments, suggestions, and inquiries, email legal@sadsadtamesislaw.com.

Author/s: Patricia Mae L. Minimo and Melissa P. Mendiola

About the author: Patricia Mae L. Minimo is the Firm’s writer. She is a Communication graduate from the University of the Philippines – Baguio with a major in Journalism and a minor in Speech Communication.